最果てのイマ (Saihate No Ima) Everyone Everywhere All At Once

18 11月 2022

The Internet as the Global Village

There's something very exhausting about accessing the World Wide Web. It's likely because we now treat it as a chore. We romanticize the days before the internet and feel nostalgia for the early days when it felt like a playground full of possibilities.

But now, we are bombarded with new obstacles hampering socialization every day.

With every step made toward advancing communications technology, we stray further from the people we know. Not only is it deeply ironic but this pattern is now a mainstay feature on social media. We use these services like Discord to find friends only to alienate ourselves; we don't know actually how to communicate in this new era after all. Instead, we're overwhelmed: there's too much information, too many social cues to follow, too many people. The internet is strangling us, but we need it.

If we couldn't access the internet, we would be cut off from the entire world. Imagine not being able to access Wikipedia: all that information at your fingertips would vanish. Sure, you can still research without the internet -- but reading books and watching documentaries can only go so far. You will become outdated because new updates on the latest research are being discussed on Facebook. The "word-of-mouth" and water cooler talk are replaced by Twitter threads and SEO-friendly articles.

And for many young people too, their first deep exposures to subject matters that won't be explored in schools (ex. sexuality, gender) aren't from books but on carrds and Tumblr reblogs. They explore issues affecting them in fanfiction posted on Archive of Our Own and get to taste criticism for the first time from watching media analysis content on YouTube. Streamers and VTubers are the new counselors of today's ailments. The fear of missing out is amplified on the web as everyone gathers around on Discord to talk about the latest movies and shows...

Everything is happening on the World Wide Web. We can't live without the internet. And yet, we despise it.

Sanctuaries of the Dispossessed

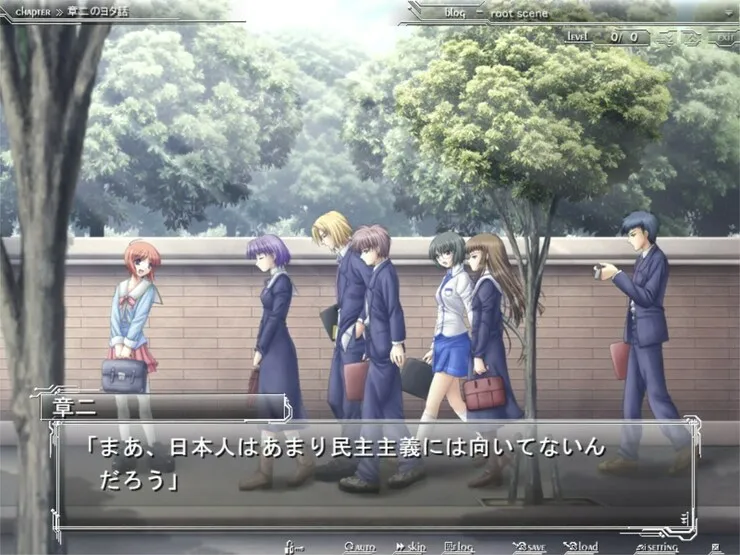

If the above soliloquy means anything to you, then you may be interested in reading more about the themes present in this particularly inaccessible 2005 title: 最果てのイマ (Saihate no Ima) by Tanaka Romeo (CROSS†CHANNEL, Kana ~Imouto~, Jinrui wa Suitaishimashita). Clearly meant for a specific subset of people who spend their days doomscrolling and reading blogs on Substack, this prescient title speculates and tackles the ongoing technological developments that affect how we perceive ourselves.

It does this in the form of blog posts that read like Wikipedia.

The work follows seven misfits who've founded a sanctuary (聖域), which is actually an abandoned factory in the middle of nowhere. Led by Atemiya Shinobu, this Breakfast Club-styled group doesn't share that many affinities with each other -- all come from different backgrounds and have unique personalities. But this sanctuary, this safe space is where they feel they belong. They can chill and express themselves. People eat snacks, talk about random shit like world politics and barbecue, and even camp there if they're tired from their family and school. Everyone came to this community because Shinobu was nosy enough to make people join his hideout. This fragile community space may dissipate someday, whether through the passage of time or major historical events, but he believes it is one worth preserving.

However, the question becomes “How much would you do to save this?” Would you sully your hands by getting into the mess of interpersonal relationships? How much research would you do in order to feel like you can lend a helping hand? Are you willing to invite your friends into a new kind of hell?

And incorporate all of that into one space?

At its core, Saihate no Ima has a simple yearning: you just wanna hang out with your buds, but you don't know how. And yet, this yearning is actually a mosaic of ideas and concepts that give birth to more of such mosaics. Questions lead to other questions. No simple answers exist when it comes to the human condition. Only complicated ones. You have to enter into rabbit holes that seem tangential to the subject matter but are ultimately necessary to answer the most fundamental of questions, "Why do relationships matter?"

As a result, the title is structured intentionally like a haphazardly written personal blog or a poorly written Kastel post unedited by Len. As you read scenes depicting Shinobu's everyday life, you will encounter hyperlinks that lead you to articles explaining concepts like Minakata Kumagawa's understanding of jashi or even fully fleshed out scenes that are part of the chronology of the game -- and these may also link to another article or scene altogether. The game is just full of <a href>s: every digression and digressions-within-digressions are unleashed upon the reader without a check in place. You are stuck in this worldview envisioned by the blog, with no compass telling you when or where this scene takes place in. It's like you're stuck in the middle of a Wikipedia article and you want to crawl your way out. Its worldbuilding appears and disappears within hyperlinks, euphemisms, and throwaway lines that would only make sense on a second reading. But chaotic and headache-inducing this may be, this is representative of how we in this internet age perceive the world.

The title is deliberately confusing because this is how we structure our lives alongside technology. Example: we are reading microblogs (i.e. the fragmented musings of everyday people detached from time and space). When we reply to someone pontificating about something, we aren't thinking of the contexts (the life story of this person) but on an idea that intrigues us. There is always the possibility of talking past the other because we aren't thinking exactly the same thing -- and technology aggravates this dissonance. And when worst comes to worst, the parties involved may feel hurt over the miscommunication. Nothing feels as bad as being incapable of translating yourself to other people correctly.

But we (and this title) still strive to communicate anyway, even if we are prone to misunderstandings. No one can truly live off the grid. We are forced to participate in the internet and thus seek reprieve within this new technological medium.

In a way, yesterday's blogs and today's Discord chats are the sanctuaries of the weak. The community it fosters is as vulnerable to harm as Shinobu's sanctuary. We gather in the comments section and praise or criticize before going on our own ways. From afar, it looks disgusting and sick -- the bartender character in The Silver Case comes to mind -- but it is the necessary act of catharsis for many online-brained people. We want to be understood and these sanctuaries are the manifestations of that very desire.

The Eroge is the Message

I bring up the eclectic ideas of Marshall McLuhan not just because the title clearly owes huge debts to his works but also it provides an avenue in understanding why the title is so preoccupied with the interplay of technology and alienation.

Though McLuhan is most famous for propagating "the medium is the message", there is a more eminent quote attributed to an unknown person that he would often use and it clarifies what he's actually getting at: "Water is unknown to a fish until it discovers air." A more dry and academic explanation by the man himself appears in War and Peace in the Global Village: “One thing about which fish know exactly nothing is water, since they have no anti-environment which would enable them to perceive the element they live in." In other words, fishes won't realize they've been in the medium known as water until they're out of the fish tank.

And like these fishes, we can't really gauge our environment. We’re looking at technologies like social media in the lens of the past, leading to this dilemma we all face. In Medium is the Massage, McLuhan called this the Age of Anxiety: "the result of trying to do today’s job with yesterday’s tools”.

What does this mean exactly?

We can search the near past and see what he means by "yesterday's tools". McLuhan theorized in Gutenberg Galaxy about the impact of the written word and how it was transmitted. Literate people began to lose their communicative abilities to appreciate movement, sound, and touch in favor of the visually written word. A massive social transformation had taken place. This writing tradition took on a life on its own and immersed its readers, still unaware that they're in such a medium, into new modes of thinking.

But many thinkers were unaware of how communication technology had changed them because they're stuck in the past. Concepts like nationalism could not have existed if people weren't writing and sharing their thoughts about what said nation is -- Benedict Anderson's Imagined Communities is very enlightening in this regard. Using this print era as a case study, McLuhan argues that it is therefore worth considering how the manners and technologies we use to communicate could change the way we perceive the world.

Such an argument may look crude if examined with detail and I think there's flaws to this historical narrative. For example, one could raise their eyebrows on the technological determinist slant, dubious sketches of indigenous people and their cultures, its espousal of certain Orientalist and cultural nationalist ideas to distinguish The West from China and the Global South, the questionable distinction between literate people and non-literate people, ambiguous definitions of important concepts like the "global village", spurious connections to random thinkers, obscurantist lines of reasoning etc.

But cut away the fluff and the crux of the argument remains intact: We are affected by our technological environment in ways we don't expect. Or to put it another way, in the background, technological innovations are hosting services and processes that's screwing with our lives. Humans are always within these mediums. The people of the past weren't directly affected by the printing press per se, but they were enveloped in the environment that the press conjured. A more modern example may clarify this further: traffic jams and car pollution don't come from the fact that we're car-dependent but rather that we're actually highway-dependent. Television (and later, social media) connects people spontaneously through audio-visual and participatory elements while reading remains a private matter. Mediums define us as much as we define them; this defining is the environment. It may not be surprising to learn then that McLuhan and his followers called their discipline "media ecology": the study of how the cumulative effects of media technology, understood as an environment, influence our thinking.

Hence, the medium is the message.

But this insight came with a warning: we too are being changed by the media environments we're in. What McLuhan fears is that we're actually 19th century human beings facing the wrath of 21st century technology. If we want to treat technology as a medium seriously like him, then we must admit we're willfully unprepared to apprehend how technology will affect us. We haven't thought about this enough. Just like the fish that won't know they've been traveling in the medium of water, we won't know what medium we're in until we're out of it. A passage from Gutenberg Galaxy elucidates us on this aspect that is especially pertinent to Saihate no Ima:

The highly literate and individualist liberal mind is tormented by the pressure to become collectively oriented. The literate liberal is convinced that all real values are private, personal, individual. Such is the message of mere literacy. Yet the new electric technology pressures him toward the need for total human interdependence.

This may read like a text predicting the rise of social media and Discord groups, but the title is a 1962 work and McLuhan passed away on 1980. He's been on the money, predating ARPANET (i.e. the first workable prototype of the internet) by around seven years.

The Internet as the Age of Anxiety

And so, we are now at the heart of the matter: the internet is a scary place that fascinates our imagination. It is a global village where we are connected to each other. While McLuhan wasn't alive to see even the earlier consequences of the internet, his insights remain far-reaching.

McLuhan specifies technologies as extensions of our bodies in Understanding Media. The clothes we wear are just extensions of our skin. We step on the gas pedal and the car becomes our body. Even expressions like "the heart of the city" suggest a deep organic connection. The computer age is especially remarkable for connecting our nervous system to the electrical systems of computers. We are one with computers. We think in and within computers and now the internet.

Or so, we like to think.

As McLuhan notes, the way we associate with one another has been sped up. Our older modes of communication could not adapt to this lightning speed. We "begin to sense a draining-away of life values" as we try to save this sinking ship. Technology will always be "extensions of our physical and nervous systems to increase power and speed", but we can't keep up -- not with our antiquated frameworks.

The internet is thus too much. Too much shit flung onto our faces, to be more precise. When we talk about information overload, we aren't actually describing it metaphorically but rather literally and sensually. Numbing is of utmost necessity in McLuhan's view; otherwise, our extensions will shock our nervous system to death. This coping mechanism has brought him to the conclusion that "the age of anxiety and of electric media is also the age of the unconscious and apathy." This is bad news, especially as we're becoming more connected to other people. But like bad Wi-Fi connecting and disconnecting our laptops, our half-assed connections are causing us to shock each other. We cannot deny other people's existence anymore because we can see and hear them.

Think about it: we enter big Discord servers full of members talking to one another and feel like we can't talk. Our words enter into a void. We feel responsible for not being connected. Technology is supposed to help us and extend to new frontiers, but it has failed us -- or rather, we don't know how to use it and we have failed it but that's a truth that hurts too much for our ears.

Our mishandling of technologies has trapped us in this fragile interdependence. We haven't figured out how the basic principles of the internet and other technologies have changed our lives for the better or for worse. How can we even hope to communicate with others when we've only just started to notice other people exist and we can hurt each other?

Technology Against Technology

With this understanding, we can now return properly to the themes of Saihate no Ima. In later sections, the title contemplates about sense-perceptions being invaded by new technological mediums. After the reader has gone through all the character routes, they are suddenly thrown into an arc all about a war.

What war?

Technology.

How do we fight against technology?

With technology.

An unconventional panopticon has arisen in the title's version of the internet. Everyone is, in some sense, connected to each other in the most terrible of configurations. Like our minds are sutured into a cyborg Twitter. Besieged within this new media/environment, people loudly wonder if free will or individual agency even exists.

Social media in the Saihate no Ima universe isn't just for marketing but a technological chimera we can unleash upon others if we have the right training. There's no need for nuclear weapons when we've volunteered to become weapons of mass destruction.

It is therefore unsurprising that everyone desires some liberation from being part of this literal hivemind.

But rejecting today's technology and the global push can feel a bit wrong. Anti-globalization efforts are politically and ethically questionable by themselves, even before the rise of the internet -- and yet, we know the effects of globalization are harmful anyway. Not only are we averring technology but we are rejecting the mode of socialization the ruling classes have picked for us. Saying no to our Facebook-ization means we have opted to ostracize ourselves. We are alone, betrayers of the human race for not signing up for the service.

If you don't join the war/social media, you are not a good soldier/poster. You're helping the enemy win against the humans.

But is it truly morally wrong to feel like we want to avoid this military draft, this duty to participate the war between technologies? Do we really want to sacrifice our autonomy in the name of globalization? In other words, are we hesitating to entrench ourselves further into this alienating space, this global village?

This war of technologies feels so grand and incomprehensible to the reader and Shinobu. And like most wars, there seems to be no good cause. The salvation of humanity feels so empty when so many people die or end up feeling cut off from the world.

All we feel is that we're missing something. The more connected we are, the more we just don't understand each other. Our environment becomes alien, our communities ruptured. Is that really the war we want to stage today?

The Alienation of Today

That is the mode of alienation this title is investigating. Without a doubt, it is a massive undertaking that will bore and excite its readers with each new scene and insight.

Saihate no Ima is not a plot-driven narrative but a battleground of ideas between Romeo and McLuhan. It is obvious that the former takes the latter's ideas seriously, but he still wants to find the humanism within this alienation, this age of anxiety. Romeo agrees with the general insights raised by McLuhan and even supplements them with social scientists as diverse as Malinowski and Levi-Strauss. Yet, he can't accept that we're all regressing/advancing into a global village. He can't see everyone ceding their human freedoms and signing the social contract to today's Leviathans at all, not even through the power of media. The main forces behind globalization may try to flatten the world through communications technology, but the world remains spiky. People must always feel the need to resist that tries to make them into one coagulation -- one giant mainstream.

In other words, Mark Zuckerberg and his staff might be able to incorporate many into their walled garden of Facebook systems -- but there will always be resistance. Globalization is merely a politically expedient way of saying neo-colonialism. It alienates people by connecting them to more people who are also alienated at the expense of other alienated people. As a result, there will always be rebels against this colonization of everyday life. They are seeking to abolish social media in order to build a better environment that respects, not gentrifies, the communities and sanctuaries we belong to.

Their hope (and Romeo's too) is their firm belief that the failure to globalize isn't the end of humanity -- or rather, the global project of humanity may have declined but it isn't the end of what is human about us. We have to think differently and perhaps perceive differently too.

Technology, in the end, is supposed to serve us. Whatever comes after our innovations defines our actual human essence. We are always searching for this speculative definition.

The Solace of Tomorrow

Perhaps, it could be found in the spaces Saihate no Ima calls sanctuaries.

These artificial and problematic constructs -- communities, UseNet groups, IRC channels, clubs -- are still bonds we desire. They may be affected by media/environmental influences, but they remain sources of respite. Predating the overall message of Caligula Effect 2 by many years, the title sees sanctuaries and other safe spaces as areas where members could roam freely and experiment. While not foolproof, these sanctuaries are at least far away from the hubbub and buzz of this ever globalizing world. Such subcultural spaces allow us to recover from traumas of an over-connected world and heal our wounds back up.

This is obviously a compromise -- even a cop-out -- regarding the issue of a global village, but sanctuaries are the current medium that we little fish are swimming in. We may not be aware that we privilege such spaces in the first place, but we absolutely need them to survive.

In this light, the real accomplishment of Saihate no Ima then is how it not only highlights this longing for a community but becomes that sanctuary. It is a sanctuary of people unsure about the value of sanctuaries. But we can go further: it is also a sanctuary of sanctuaries for all the people unsaved by the apocalypse of a technology-induced solitude. The title wants readers to realize their dependence on sanctuaries and also, like the nosy Shinobu, invite them to stay in its space.

Its raison d'etre is thus very simple: McLuhan talks about how art functions as an "anti-environment" and a "radar" of the future. In War and Peace in the Global Village, he expands on the role of the artist as

the only person who does not shrink from this challenge. He exults in the novelties of perception afforded by innovation. The pain that the ordinary person feels in perceiving the confusion is charged with thrills for the artist in the discovery of the new boundaries and territories for the human spirit. He glories in the invention of new identities, corporate and private, that for the political and educational establishments, as for domestic life, bring anarchy and despair.

To summarize: art is intended to remind people technology affect us. The artist is a courageous explorer of the new and weird -- they pull the reader into the current times. The sanctuary of Saihate no Ima works exactly like this and Romeo/Shinobu is dragging us/friends to experience the present once more.

There is a hint of Romeo-esque solace in this abolition of the past: we may be working toward the present, but we're actually preparing for the future. Understanding today is really about getting ready for tomorrow. Engaging with our modern gadgets and thinking through their implications means we can actually predict the future.

Art thus allows us to peer into the future and Saihate no Ima certainly fits this bill.

A Conclusion Beyond Tweets

But all this armchair philosophizing by an untrained pseudo-academic aside, what do I actually think about the title itself?

To be quite honest, I don't like Saihate no Ima that much.

It is frustrating and unsatisfactory to recommend to anyone but the most dedicated of Romeo fans. Notably, Romeo was unable to finish the middle chapters; we can only read the beginning and end. It's a title better approached as a collection of thinkpieces and essays on various social science fields rather than a story with cathartic moments. The chronological sequence of events is hard to follow due to plot reasons and I have, at times, thought about doing something else. I only stuck around because I'm just a stubborn asshat.

If anything, I feel like I've undersold how dull this work can be. I am a yuributa after all; I need them cute girls hugging and kissing each other. My exasperation is immense, man.

However, perhaps due to its unconventional nature, the flights of fancy and sparks of imagination it offers are unparalleled among all visual novels. There is much to criticize, but there is also much to be awed by. While I could've deservedly rattled on about the inaccessibility of this title, I cannot hide my admiration for this work.

I've been in online spaces for ages and these themes resonate with me a lot. I've seen rises, falls, gossips, libels, love, harm etc. sprout in the many sanctuaries I've wandered into. Reflecting on my own alienation is a past-time I engage in too much. I've thought long and hard about philosophical movements like Xenofeminism, which argue that we should use this alienation as a jumping point to fight for new futures. My online-poisoned comrade, curry, in fact thinks that Romeo has actually enunciated what they've always wanted to express and do -- indeed, curry specifically recommended me to read it because we share similar internet brainworms. The work has definitely made an impact on curry and me, having taken the time to meditate on its ideas. We have slightly different interpretations, but we both agree that we want to reprioritize what we want out of our social relationships.

And so, we come to this moment: I originally procrastinated on finishing this essay months ago because it's such a dense essay to edit. But with the possible death of Twitter looming over us, I figured this essay on social media should come out now.

Reading this again, I affirm Saihate no Ima is by no means the best Romeo work -- that's still Jintai for me -- but I see it as the foundation of everything Romeo's humanism stands for. He cares deeply about the alienation manifesting from technology, capitalism, and us being us. There are no good solutions to this fundamental problem, but he respects what all of us do in order to remain connected in an over-connected world.

And as I write this, people are writing about how Twitter will fade from existence soon. I know friends are packing up their bags to go elsewhere or they're staying put till the end. It seems clear that a paradigm shift in social media is happening.

But as for me?

Saihate no Ima taught me that I don't really care about social media. Sure: I've made friends, found a partner, and even learned new things from Twitter and elsewhere. But those joys are long past me. I don't think I've become a boomer in this regard; I just think social media is pretty pointless and dehumanizing. Unless there's good reason to sign up, I'll pass.

Switching to another social media platform for the sake of it feels like I'm postponing the problem: I want to find sanctuaries. If I can't find sanctuaries, I'll build them like Shinobu. There's no need for me to immediately join Co-host, Dreamwidth, Reddit, Discord public servers etc. for that matter. I may find like-minded individuals there to invite to my sanctuary, but that's it. All I'm interested is building a sanctuary, a comfy space that I can call home.

What will that sanctuary look like? I don't know, and Shinobu clearly didn't either. That uncertainty is what makes it exciting and perilous: building a community space like that is tough and that's why we go to social media platforms in the first place. We believe that corporations could do the tough work for building communities and perform the necessary moderation for us.

But Twitter has declined because it couldn't. It never did.

It's up to us to build the sanctuaries we've always dreamed of -- to find what is truly human about us.